Focus on the Green Energy Sector is extremely laudable and India appears to be is on its way to achieving its target of 100 GW of solar energy by 2022. Other latest developments in the Sector have also been very encouraging. Tariffs of solar energy have plummeted to Rs 1.99 per unit from the high of INR 14 per unit a few years ago. The overall energy sector is under stress but the demand for solar energy seems to be on the rise. However, to say that renewable energy has already become cheaper than coal-based thermal energy, as Rahul Tongia from Brookings India put it, “masks…system-level costs as well as the disproportionate impact (it had) on selected States’ generators and stakeholders”. Accordingly, before blowing the victory bugle there is a critical need to examine the implications of what was happening.

What are the direct and indirect costs incurred due to shifting of focus on renewable energy?

Who is bearing this cost?

Is the manner in which renewable energy mission was being rolled out in the country sustainable?

As Coal Secretary, Government of India, I was convinced that solar energy would play the most prominent role in the push for green energy. Not only did it have a larger share of India’s targets, but it also represented much of the growth of renewable energy. It was in the fitness of things that the government was pushing for solar energy.

However, I was (still am) against the mad rush for solar energy without taking into account all the associated features. There is indeed a dilemma as any reservation or difference of opinion against this mad rush is also deemed an ‘opposition’.

There is no doubt about the fact that India is a ‘sun-rich’ country with bright sunshine available for the better part of the year. However, I am equally convinced that there would still be issues that need to be considered and sustainable solutions to those needed to be developed as we proceeded towards increasing our dependence on solar energy.

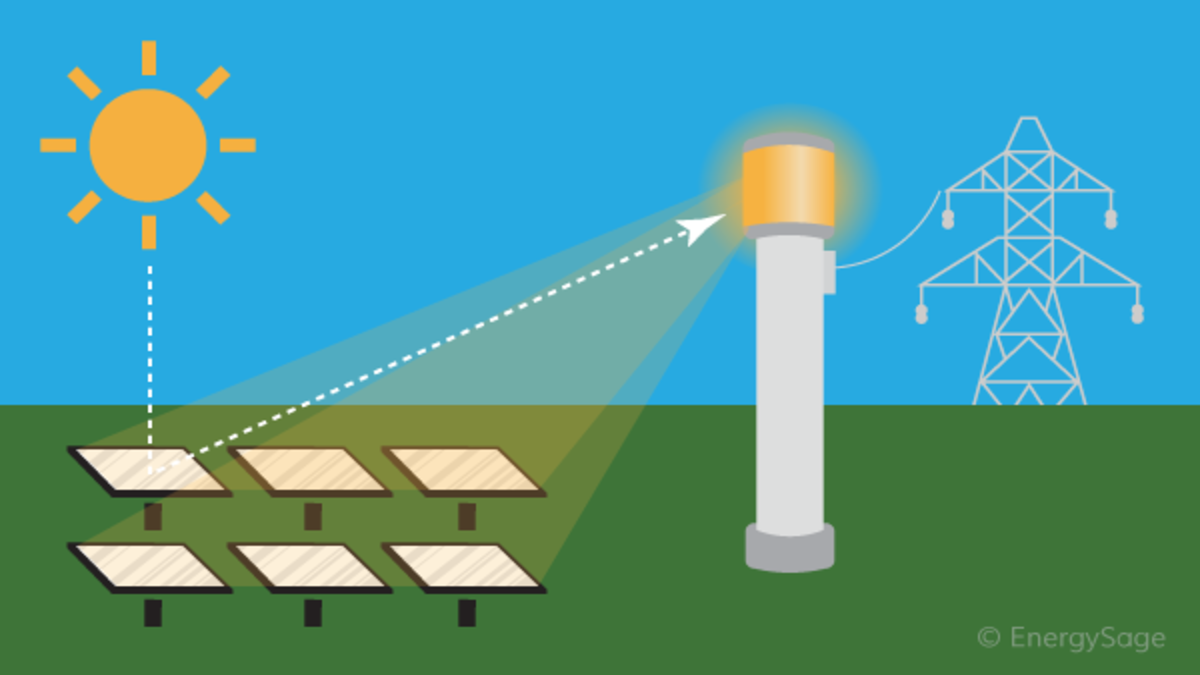

Sunlight, by nature’s law, is available only during the day. Unlike the European countries that were pushing for green energy, the peak demand in India is during the evening when solar energy (unless stored) is not available. Storage and the cost thereof therefore would be key determinants for the sustainability of solar energy, especially as its share scaled. Hydropower generation has been a good complement and India always had enormous potential. However, unfortunately, this potential has not been tapped, ironically on account of environmental considerations. (The recent cloud-burst in Garwhal region and the consequent flash floods have made the task even more difficult.) The ongoing projects, like the one at Subhanshree in Assam, have languished and the delays have led to cost escalation that have perhaps made the project unviable. India even lags in the deployment of pumped hydro capacity, the most proven and cost-effective large-scale storage technology available then.

The first step for higher solar usage is improving predictions. However, even perfect predictions can only go so far. We know monsoons reduce the output, and also sunsets. India needed to step up its game for learning to balance variable renewables as other countries have done. But we lack some tools to do so, such as flexible markets and dynamic pricing – most power is sold via static Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs).

The highest Plant Load Factor (PLF) for solar power plants is considered to be only about 20%, and many rooftops accounted for even less. Meaning thereby that the 100 GW installed capacity is only equivalent to 33 GW of thermal power (assuming it had thrice the PLF, of, say, 60%). Solar energy can produce nearly 100 GW only for a short while during the middle of the day.

Going forward, price ‘grid parity’ would be another issue that will have to be resolved. To meet peak demand in the evening, some other source of power will need to be built. Similarly, when solar power is available (typically during the day), some other power source has to back down. Both have a cost. And someone would have to bear the cost.

Rooftop solar plants sound exciting but would sound the death knell for the power distribution companies, who risk losing their best customers. These small localised solar plants will use the conventional power grid like a battery as these solar plants can generate energy only when the sun is shining. The ‘net metering’ would have enabled them to push power into the grid when the requirement is relatively low and there is ‘surplus’ power. This could lead to what has been termed as ‘utility death spiral’. There are also other issues related to setting up of solar plants as well as financing those. However, everyone seems to be rushing in. But there is some resistance from States as well as the distribution companies.

Does solar equipment perform as envisaged? There have been known issues related to the maintenance of solar panels, especially in the context of dust and pollution. The quality of solar panels manufactured on a mass scale are already causing problems. Land costs, availability, and bankability are also growing concerns, especially as India looks at scaling its share of solar energy. It’s important in this context to take into account the fact that the demand of 175 GW is projected for 2022 only. It will inevitably grow in future. Moreover, the cost of delivering solar energy is more than its generation cost. The transmission cost at 20% PLF will have to be factored in while arriving at the actual cost of shifting to solar energy.

What has been the response to these challenges? Yes, there is an enormous amount of research taking place in the western world and in China to find the ‘storage’ solution that is critical to the sustainability of this ‘solar drive’. The rest of the world is waiting with bated breath as the power of solar energy is being unleashed.

However, not many seem to be bothered about the adverse impact this undue adulation of solar energy is causing to the coal-based power plants that account for most of the energy requirements of the country. The generation companies (Gencos) are already in trouble on account of a shortage of coal and growth in demand not good enough to service investments made. It was estimated that more than INR 1.7 lakh crore of capacity could become non-performing asset (NPA). These Gencos are being pushed further by the ever-increasing coal cess, statutory ‘back-down’ to accommodate renewal energy and competition with a subsidised sector.

Green energy is the way forward but it is not likely to end the need for coal-based thermal plants in India. Not at least in an overnight manner. Hence, it would not be advisable to promote it at the cost of pushing thermal power plants to become unviable. The two have to co-exist and supplement each other, at least for the time being. The dependence on coal-based thermal power plants will gradually need to be phased out over the next couple of decades.

Anil Swarup has served as the head of the Project Monitoring Group, which is currently under the Prime Minister’s Offic. He has also served as Secretary, Ministry of Coal and Secretary, Ministry of School Education.