With the triumphant stride towards a Uniform Civil Code (UCC), Uttarakhand has engraved its name in the history as the vanguard of progressive legal reform in Independent India. Although Goa is governed by a UCC (Portuguese Civil Code, PCC), the Assembly did not pass any law and retained the PCC even after its liberation in 1961. The saga of UCC is one adorned with aspirations, but bedeviled by the quagmire of vote-bank politics. Time and again, the fulcrum of opportunity presented itself, only to be fumbled by the caprice of political expediency. The sagacious advice of the Supreme Court to implement the UCC, fell upon deaf ears, as the legislative inertia relegated Article 44 of the Constitution to a state of perpetual dormancy. Yet, against this backdrop, Uttarakhand’s resolute stride towards a UCC stands as a beacon of hope, a testament to the indomitable spirit of progress. In this column, I will dissect the legal bedrock upon which the UCC stands, and to elucidate its profound necessity in the contemporary milieu.

Constitutional History

The Uniform Civil Code (UCC) was deliberated as Article 35 in the Constituent Assembly, but discord thwarted consensus, deferring the matter to individual states for future enactment. Article 44 within the Constitution’s Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP), mandates the State to strive for a uniform civil code across India, with the term “shall” emphasizing its obligatory nature. Despite constitutional imperative, the dream of a unified legal framework remains elusive, entangled in the complexities of political will and societal dynamics.

Why the UCC?

The imperative for enacting a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) emanates from a myriad of compelling reasons which may be elucidated as follows-

1. Firstly, to foster equality among citizens navigating disparate personal laws- Despite bigamy stands proscribed under Section 494 of the Indian Penal Code, the Muslim community finds itself granted latitude to contract multiple marriages, up to four, during the subsistence of earlier marriage. This anachronistic allowance has rendered Muslim women acutely vulnerable, their lives ensnared within a web of uncertainty and exploitation. Indeed, this lacuna has even precipitated opportunistic conversions to Islam solely for the purpose of contracting additional marriages, a practice decried and denounced by the judiciary itself. The clarion call for a UCC, echoed resoundingly in landmark cases such as Sarla Mudgal v. Union of India (1995 AIR 1531) and Lily Thomas v. Union of India (AIR 2000 SC 1650), wherein the Apex Court beseeched the government to rectify this egregious disparity, and usher forth the era of equitable justice for all.

2. Secondly, in the complex web of personal laws, the pernicious practices of triple talaq, nikah halala, and iddat cast a shadow of injustice upon women, bereft of legal recourse. Triple talaq, even for trifling matters, renders wives disposable at the whims of their husbands. Nikah halala, a grotesque ritual demanding a woman to marry and consummate with another man merely to reconcile with her former spouse, epitomizes the degradation of marital sanctity. Meanwhile, iddat often translates into prolonged suffering for divorced or widowed women. Yet, glaringly absent from this legal landscape is any semblance of parity for their male counterparts. Considering such situations, the Supreme Court in the landmark case of Shayara Bano v. Union of India (2019) 9 SCC 1, urged the Centre to expedite the enactment of a UCC.

3. Thirdly, in the realm of Muslim personal law child marriage finds a disconcerting foothold. Here, the marriageable age, shockingly pegged to the onset of puberty, often around the tender age of 13, serves as a stark reminder of the glaring contradictions within our ostensibly civilized society. Indeed, in the name of religious freedom, such egregious transgressions against fundamental rights of the most vulnerable members of society, our children, cannot be countenanced.

4. Fourthly, the discriminatory nature of adoption laws within certain personal codes emerges as a troubling reality. Under Islamic law, adopted children are not accorded equal status to biological offspring, while women are denied the right to adopt altogether. Islam, Christianity, Judaism and Zoroastrianism in stark contrast to the principles of equality enshrined in modern legislation, such as the Juvenile Justice (Care And Protection of Children) Act, 2000, prohibit adoption. Due to this dissonance between religious doctrine and modern legal frameworks, the Supreme Court in the case of Shabnam Hashmi vs. Union of India (2014) 4 SCC 1 underscored the urgent necessity for a UCC

5. Fifthly, in the intricate tapestry of guardianship laws, a glaring disparity emerges, disproportionately affecting unwed mothers within Christian and Muslim communities in India. Unlike their Hindu counterparts, who are the natural guardians of their illegitimate children by virtue of their maternity alone (section 6(b) of Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956), Christian and Muslim unwed mothers face a stark disadvantage. Recognizing this inequity, the Supreme Court in the case of ABC Vs. State (NCT of Delhi (2015) 10 SCC 1 emphasized the urgent imperative for a UCC.

6. Sixthly, one of the most glaring disparities faced by women under various personal laws manifests in the realm of succession. In Islamic law, for instance, daughters are allocated only half of what sons receive. Similarly, under the Hindu Succession Act of 2005, a perplexing scenario unfolds. If the son dies intestate, father being the class II heir, will be denied any share in the property during the mother’s lifetime.

7. Seventhly, in the intricate web of maintenance laws governed by personal codes, justice often remains elusive. Maintenance amounts that fall short of addressing basic needs cannot be deemed justifiable. In Islamic Law, the practice of offering the mahr as maintenance epitomizes the highest injustice, failing to adequately support the recipient’s needs. This injustice was starkly highlighted in the landmark case of Mohd. Ahmed Khan vs. Shah Bano Begum, AIR 1985 SC 945, prompting the Supreme Court to implore the government to enact a UCC. Similarly, multiplicity of maintenance provisions across various Acts applicable to Hindus like HMA, 1955; HAMA, 1956; and CrPC, 1973 is manifestly arbitrary.

Eighthly, illegitimacy of children born out of void and voidable marriage or children born in live-in relationships.

Ninthly, the glaring absence of legal recognition for modern relationship dynamics, such as live-in partnerships, save for scant acknowledgment under the Domestic Violence Act of 2005, casts a shadow of vulnerability upon both partners, especially concerning children born within these unions. I have encountered firsthand cases exemplifying the harrowing repercussions of such lacunae. In one instance, a male partner abruptly abandoned his female counterpart after a five-year cohabitation, revealing a prior marriage and children, a devastating revelation for the unsuspecting female partner. Similar scenarios unfold when individuals enter relationships under false pretences, concealing their true identities or marital statuses. As the couple merges under one roof to gauge compatibility, the discovery of hidden truths often leads to strife, coercion, and even instances of forced conversion.There are also instances of blackmailing and extortion in the name of filing false rape cases by the female partner.

Current scenario

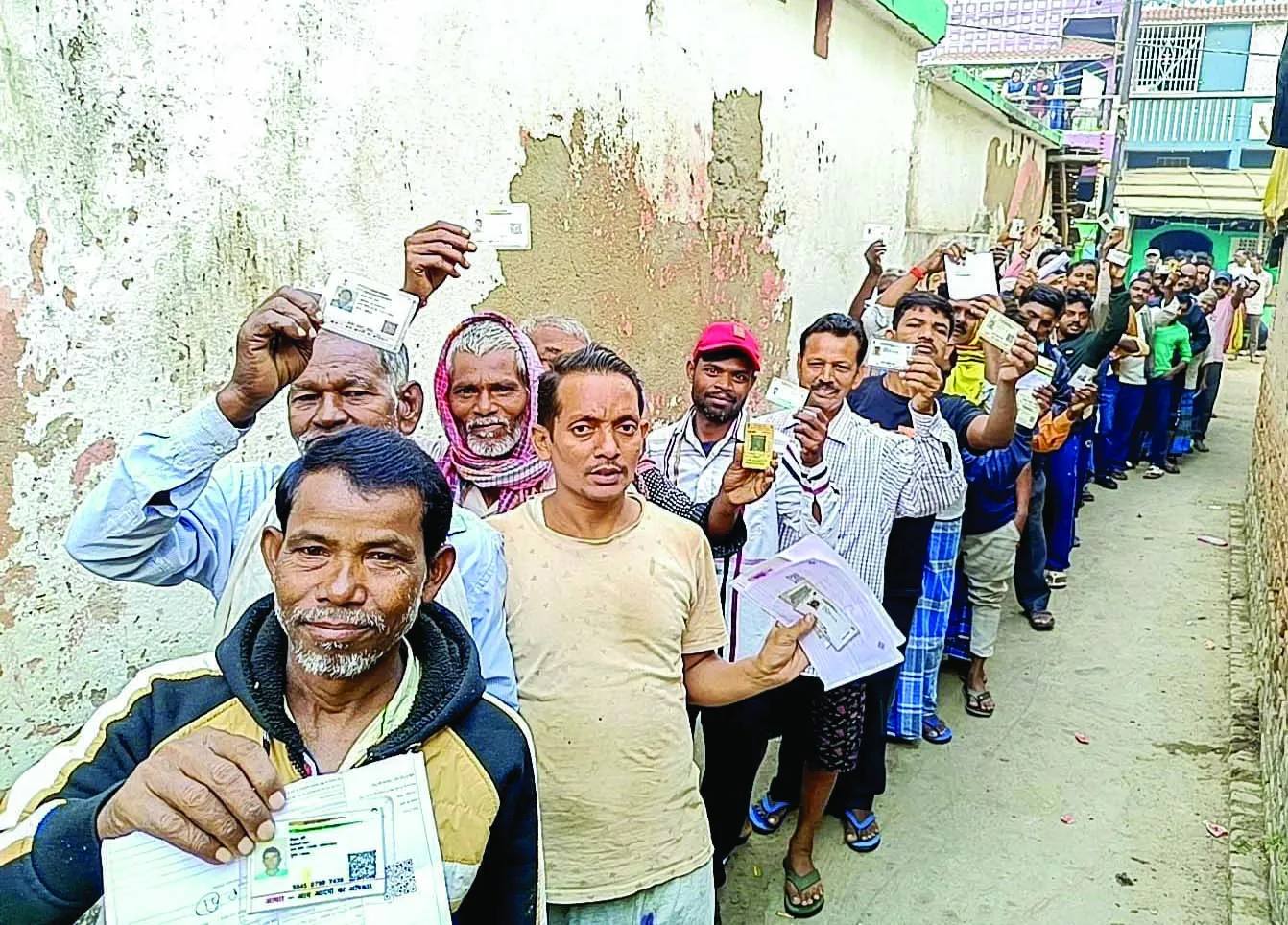

Amidst contemporary landscape, with the guiding light of Supreme Court judgments and the constitutional mandate echoing through Art. 44 read with entry 5 of the concurrent list of the seventh schedule of the Constitution, Uttarakhand’s government has taken a decisive stride. Following the insightful report of Justice (Retd.) Ranjana Prakash Desai, the state has passed the UCC. Now, as per Art. 254(2) of the Constitution, the Code has been sent for the President’s approval as it replaces many Acts passed by the Parliament on the similar issue. Once implemented, this Code will govern all residents excluding STs of Uttarakhand, regardless of religious affiliation. The government’s resolve in undertaking such commendable action deserves wholehearted commendation. In the ensuing column, I shall delve into the nuanced terrain of privacy and the right to freedom of religion.

Kumar Piyush Pushkar, Advocate, Supreme Court