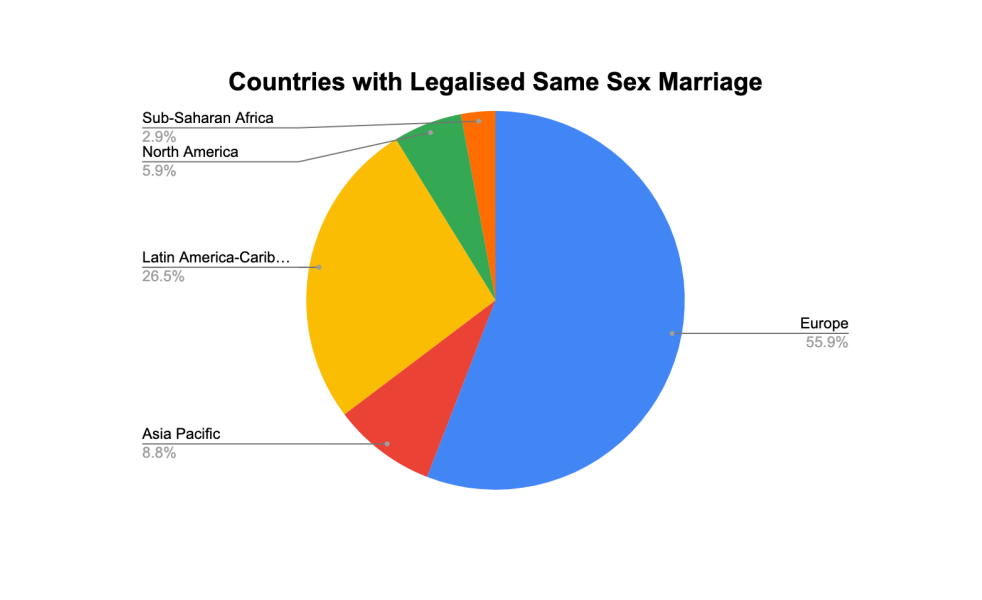

A five-judge bench led by Chief Justice of India (CJI) DY Chandrachud on Monday unanimously ruled against legalising same-sex marriage in India. The bench on 17 October also ruled in a 3:2 verdict against civil unions for non-heterosexual couples.

Activists and those from the LGBTIQA+ community were hoping for a decision in their favour while others were rooting for the Supreme Court’s current verdict as, according to them, legalising same-sex marriage would have distorted the social fabric of the country.

Tuesday’s ruling followed a petition arguing that the failure to recognise same-sex unions violated LGBTQ people’s constitutional rights.

While the court stopped short of allowing equal marriage, it recognised the rights of gay couples. The ruling means that Indians will now be free to engage in same-sex relationships, assured of constitutional protection. But marrying someone of the same sex remains forbidden. Chief Justice Chandrachud said the right to choose a partner was “the most important life decision”. “This right goes to the root of the right to life and liberty under Article 21 [of the Indian Constitution].”

DIVIDED PUBLIC OPINION

According to a survey conducted by Pew Research Center earlier this year, 53% of adult Indians are in favour of legalising same-sex marriage. Within this group, 28% “strongly favour” and 25% “somewhat favour” the move. On the other hand, 43% were completely against such marriages, with 31% “strongly opposing” and 12% “somewhat opposing” the idea.

The survey results were considered a significant boost for same-sex couples and their allies in the country. On the other hand, the Union government has opposed the legalisation of same-sex marriages, saying it goes against Indian culture and the heteronormative framework of sexual relations. Currently, homosexuality is decriminalised, yet the marriage between two adults of the same sex is not legally recognized.

The survey has also found that a total of 12 countries surveyed, adults under 40 were more likely to support the marital union of homosexuals. However, there are significant differences in terms of age in other countries. Indian laws define marriage as a union between a man and a woman. Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalised homosexuality, was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2018, a landmark victory for LGBTQ+ rights in the country. However, the decriminalisation of homosexuality did not legalize same-sex marriages. Several legal cases have been filed in Indian courts seeking to legalise same-sex marriage, but as of now, the courts have not granted legal recognition to same-sex couples.

In 2017, the Delhi High Court declared that same-sex couples were entitled to be in a stable relationship, but stopped short of legalising same-sex marriage. In 2020, the Indian government introduced the Personal Data Protection Bill, which includes a provision recognising the right to privacy as a fundamental right. Some legal experts speculate that this provision could be used to argue for the legalisation of same-sex marriage, as it acknowledges individuals’ right to control their personal lives.

HISTORY OF LEGISLATION

The history of LGBTQ+ rights in India dates back to the colonial era when the British introduced Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code in 1860, criminalising homosexual acts. This law persisted even after India gained independence in 1947, leading to certain prosecutions of LGBTQ+ individuals for over a century.

KEY EVENTS

Several key events have shaped India’s approach to LGBTQ+ rights:

The introduction of Section 377 in 1860, criminalising homosexual acts and founding of LGBTQ+ organizations, including the AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan (ABVA) in the 1990s.

The Naz Foundation’s public interest litigation in 2001, challenging the constitutionality of Section 377. The Delhi High Court’s landmark decision in 2009, declaring Section 377 unconstitutional and decriminaliSing homosexuality.

The Supreme Court’s 2013 decision overturning the Delhi High Court’s judgment, reinstating Section 377. The Supreme Court’s 2018 decision declaring Section 377 unconstitutional once again, decriminalising homosexuality.

Despite these legal victories, same-sex marriage remains unrecognised in India, denying LGBTQ+ couples legal and social benefits. These events have played a significant role in shaping India’s approach to LGBTQ+ rights, from the criminalisation of homosexuality to the decriminalisation and eventual legal recognition of LGBTQ+ individuals.

However, challenges and discrimination still persist, and there is a need for continued advocacy and activism to ensure equal rights and protection for the LGBTQ+ community in India. The Indian government has not yet legalized same-sex marriage. However, in 2017, the Delhi High Court ruled that the right to marry is a fundamental right and that denying same-sex couples the right to marry is a “violation of their rights”.

A majority view on the five-judge Constitution Bench which decided the same-sex marriage case held on 17 October that non-heterosexual couples cannot claim an unqualified right to marry. Though all five judges agreed that homosexuality was neither an urban nor elitist concept, they differed on the point of whether the court could obligate the State to formally recognise the relationship of queer couples by giving it the legal status of a “civil union” or “marriage”. The minority views of Chief Justice Chandrachud and Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul held that constitutional authorities should carve out a regulatory framework to recognise the civil union of adults in a same-sex relationship.

The two judges held that the right to enter into a union cannot be restricted on the basis of sexual orientation. Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is violative of Article 15 of the Constitution, Chandrachud said during the proceedings. The majority views of Justices SR Bhat, Hima Kohli and PS Narasimha disagreed, holding that it was for the legislature, and not the Court, to formally recognise and grant legal status to non-heterosexual relationships. However, all five judges agreed that the Special Marriage Act of 1954 was not unconstitutional for excluding same-sex marriages. They said that tinkering with the Special Marriage Act of 1954 to bring same-sex unions within its ambit “would not be advisable.”

SC verdict on same sex marriage

1. Queerness is a natural phenomenon, it is not urban or elite

2. Constitution does not recognise fundamental right to marry

3. Court cannot strike down Special Marriage Act 1954 or read words into the provisions of SMA

4. Freedom of all persons to enter into a union is in the constitution

5. Article 15 (1), the word sex must be read to mean sexual orientation

6. The right to enter into a union cannot be restricted because of sexual orientation

7. Unmarried couples can adopt, this will include queer couples

1994

ABVA, an NGO, files petition in Delhi HC seeking repeal of Sec 377, after Tihar male inmates denied condoms: fails to follow through

2001

PIL by Naz Foundation in Delhi HC seeks repeal of British-era Sec 377. around since 1862

2004-2008

Back & forth in courts

HC dismisses petition

Activists move SC, which asks it to reconsider

Centre plays for time; home, health ministries file contradictory affidavits

Centre submits gay sex is immoral, argues against decriminalisation

HC shoots down ‘immoral argument, calls for scientific evidence

Centre says Parliament must decide

JUL 2, 2009

Delhi HC decriminalises homosexuality

2009-2012

Religious groups. individuals challenge SC’s decriminalisation verdict

DEC 11. 2013

SC sets aside 2009 Delhi HC order, leaves matter for Parliament to decide

2015

Lok Sabha votes against introduction of private member’s Bill by Congress MP Shashi Tharoor to decriminalise homosexuality

FEB 2016

3-judge SC bench says all pleas will be reviewed afresh by a 5-judge constitutional bench

AUG 2017

SC upholds right to privacy, says sexual orientation is an “essential component of identity” and the rights of LGBTQ persons are “real rights founded on sound constitutional doctrine”

2018

SC decriminalises homosexuality

SC bench headed by CJI Dipak Misra says 2013 ruling to be reconsidered, sends it to larger bench

SC says it’s up to bench to take a call on the 150-year- old ban on gay sex