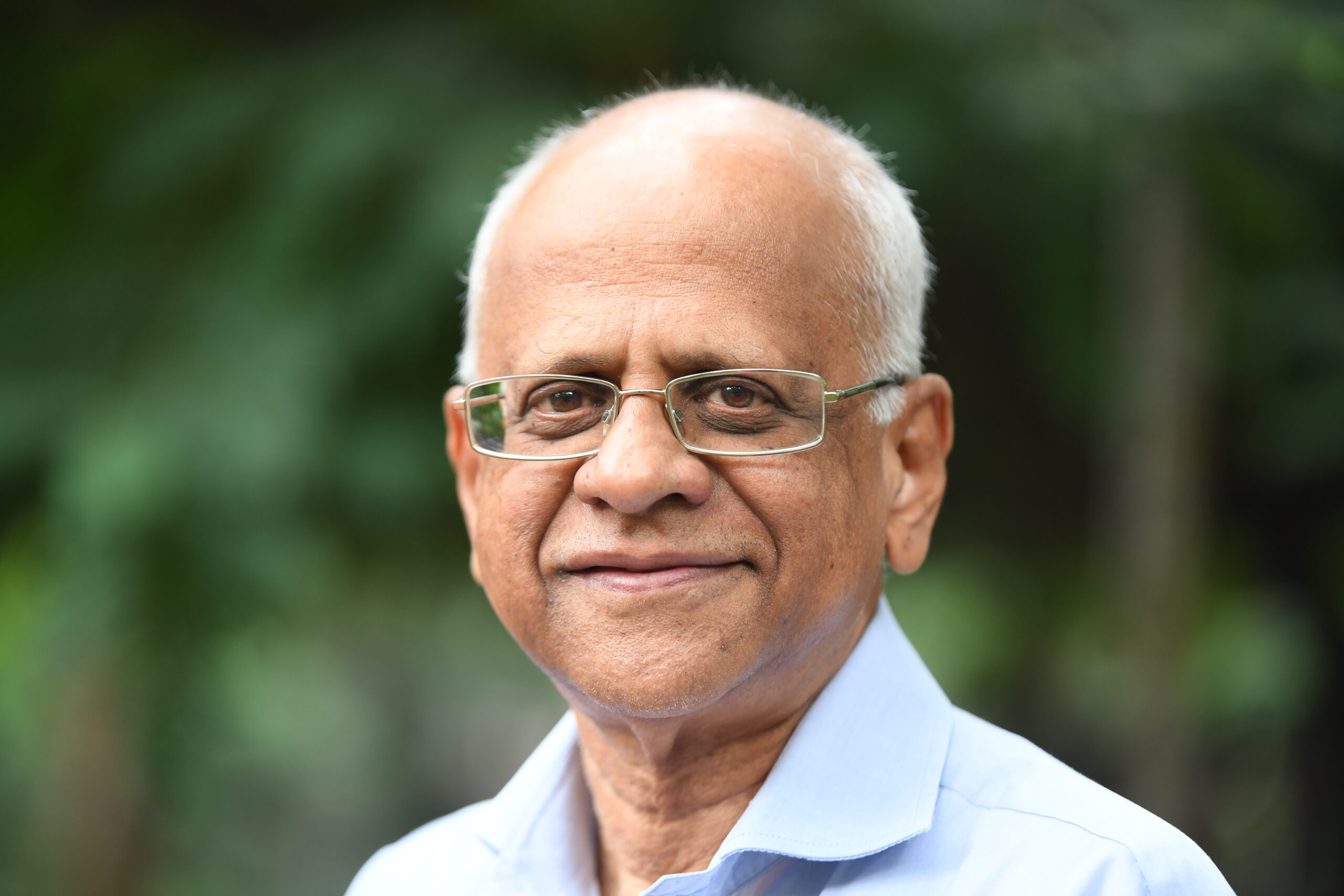

Prof.Gautam Desiraju, a well-known Indian scientist and crystallographer who has made significant contributions to the field of chemistry, recently reviewed modern day India and its constitution in his book Bharat: India 2.0, promulgating the restructuring of the map and therefore the states for better governance. In the book, Desiraju proposes a redrafting of the constitution, highlighting the faultlines. The professor also demonstrates the limitations of the current model of governance and proposes a unique solution of 75 states with equal populations. He further suggests that a country like Bharat cannot progress both economically and culturally without being in harmony with its civilizational identity.

In a recent interview, we got to talk to Prof. Desiraju about his new book.

Q. There are conversations around how the constitution is the most talked about but rarely understood, and here we have you deciphering that constitution as not sympathetic to the civilizational nature of Bharat. What made you take this journey through Bharat 2.0?

A. Yes, the Constitution is talked about in the sense of it being some kind of holy book, that it’s immutable, that we must worship it, that Ambedkar wrote it from start to finish, and because of that we must have reservations forever, that it says we are a secular country, whatever that means, and that there was no India before 1947. There is more confusing stuff going around today that we are a “Union of States” which is what we actually are, but the meaning of this phrase as given today in certain quarters is completely distorted from the original Constitutional meaning, which is accurate. A lot of fuzzy and vague things are also talked about, with just a hint that the Constitution is all that an obscurantist old faith called Hinduism is not. There is also a lot of informal chatter that religion, especially Hinduism, prevents us from being modern and progressive. All these things and more I’ve been hearing for the better part of 50 years. This was essentially the Congress ‘idea of India’. So I wanted to set the record straight, at least from my viewpoint. For a start, I guessed that most of us weren’t even familiar with the Constitution or understood terms like democracy, republic, secular, sovereign or socialist. Do we even know that India had a rich constitutional history for 50 years before independence? I also felt that the most vital part of Bhārat, namely its civilization was not revealed in the Constitution, which looks like a mish-mash of several foreign constitutions.

Q. The need to divide larger states into smaller states has been felt for administrative purposes, and you propose a model of 75 states. What are the broad characteristics based on which you propose the divide?

A. As you say, there is no question that smaller units are easier to administer, and India’s states are way too large. The book gives examples of more compact units in the USA, Italy, and especially Switzerland, where smaller units permit higher degrees of autonomy, which in turn allows for efficiency and a higher quality of life for citizens. Now about the number 75, this is a number that evolved naturally. It could be 70 or it could be 80, but 75 is a number I arrived at by considering history, geography, mythology, culture, language, ethnicity, religion, existing demands for statehood, and also, quite importantly, the ability of these smaller states to develop a niche area where they could maximise economic strength through any or more of the following: manufacture, agriculture, mineral wealth, tourism, textiles, shipping, geostrategy, commerce, solar energy, and so on. The idea is that by having 75 small states with highly specialised industrial or commercial outputs, we would generate 75 economic powerhouses, each of which would rival an entire country. For example, Kashmir in the north would compete with Bulgaria in the matter of lavender and rose oil; Kutch in the west could take on Israel in solar energy generation; Kongu in the south would equal or better Bangladesh in textile manufacture; and Kashi in the east would surpass Vatican City in religious tourism. With 75 small monolingual states, the problem of linguistic chauvinism would, I feel, go away forever.

Q. Political discourse already sees the south-north India fight, the Punjab Khalistan issue, and the West Bengal issue based on demographic change; how does the book address the issue of the fragmentation of the country further?

A. It might appear counter-intuitive, but having smaller states, based on microdiversity differences, would actually lessen the likelihood of fragmentation, or what is called Balkanisation. Bhārat is a very diverse land. This diversity is our strength, and we are not optimising it in our administrative structures. My scheme for 75 states envisages the population of each of these states to be nearly 2 crore. A state this small has little chance of exhibiting separatist tendencies, and quite practically speaking, it would not be viable as a sovereign country. In the book, I have also asked for increased latitude to be given to the Centre in the matter of imposing President’s Rule, untrammelled by the Supreme Court, in the event a small state exhibits the slightest inclination to secede from the Union. The next point is that Sanātana Dharma is itself based on microdiversities that come together in a grand synthesis where the overall panorama is that of the land we call Bhārat. The little states I have drawn will enjoy their diversity in their small domains and yet also feel comfortable as Bhāratiyas in a very vast domain called Bhāratavarsha. Bhārat is not a nation state. It is a civilisational state. The question you may ask is, what is wrong with 28 states? Do they not show diversity? The problem with 28 states is that now we have some states mostly bordering neighbouring countries or having maritime boundaries that are politically too strong. When an opposition party is in power in such a state, it starts disturbing the big national agenda for purely short term political reasons, and this is severely against the national interest. Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Kerala, Punjab, and, until recently, Maharashtra, come to mind. States need to be economically strong, not politically strong. The centre needs to be politically strong, while its touch on the economy should be light. This economic role should be confined to currency management, broad fiscal policy, defence, atomic energy, space, and trying to relate our economy with our international and geostrategic relations. We have the opposite situation. The states are politically strong, and the centre is economically strong. The centre decides all sorts of detailed financial matters for the states. With 75 economic powerhouses, the states will become rich and not waste their time proclaiming Tamil superiority, Bengali superiority, or whatever dissipative things they do today in an attempt to garner votes in the next election. So, no, I am of the firm feeling that 75 states will not lead to Balkanisation.

Q. There have been divisions of states, forming Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, and Telengana. Do you see a successful transition to state identity and, therefore, national identity?

A. The problem in Jharkhand and Uttarakhand seems more to be a succession of bad and corrupt state leaders than the fact that they are small states carved out of larger states. We note that the demand for a separate Jharkhand is more than a century old—in other words, way before independence. My suggestion for Jharkhand is that if it manages its mineral resources in a modern, technological way like, say, Australia, it can become richer than Australia. The niche area for Jharkhand is minerals, metals, and rare earths. They are doing hardly anything in these areas and seem to be worrying more about elections and toppling governments. Similarly, Uttarakhand has been unlucky in having had a string of bad chief ministers, whatever their political affiliations. There is no doubt that the people of the hill areas wanted their own state, and the separation from Uttar Pradesh is never criticised. Uttarakhand is one of seven or eight states that I have left untouched in my division of Bhārat into 75 states. People have to show their dissatisfaction with corrupt and inefficient leaders. The problem is not having a smaller state. Telangana was the inspiration for me to write this book. The fact that the first linguistic state, namely AP, was also the first state to be divided into two states speaking the same language (outside the Hindi speaking areas), is surely an indication that Bhārat has outgrown the idea of language as a marker of diversity. Telangana is far advanced with respect to Andhra Pradesh now (possibly because Hyderabad is located there, I will admit), but this should only encourage Andhra Pradesh to develop a megacity or several smart cities to take it ahead. Then it will be a win-win for everyone. Again, the problem is not small states per se.

Q. You differentiate between a country and a nation, defining India as a country and Bharat as a nation. Please elaborate on how the two are different.

A. A country is a political entity that is demarcated by accepted international borders. A country is associated with sovereignty, or, in other words, its ability to defend its borders, establish law and order within them, impose taxes, and manage its currency and trade accordingly. India is a country. Citizens of a country are entitled to a passport and other marks of citizenship. A nation, on the other hand, is any agglomeration of people who are linked by a certain idea of identity or kinship. Sometimes the boundaries of a nation coincide with the limits of nationhood. Then you get a nation-state, for example, France, Germany, or Serbia. The nation-state is a European idea that follows from the Thirty Years War and the Vienna Congress. Sometimes a nation does not correspond to a country. For example, the Tamil nation is a group of individuals in India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Singapore, or even the USA who feel a sense of identity as Tamils. There is no country that corresponds to such a Tamil nation. India is not a nation state. But the idea of nationhood does exist among us, and it is a larger concept than being a citizen of India and holding an Indian passport. Our nationhood is best expressed in terms of us being Bhāratiyas, and therefore I affirm that Bhārat is the best term to express our national identity.

As told to Lipika Bhushan, senior publishing professional, founder MarketMyBook and children’s author. She can be found on twitter @LipikaB