Indian National Congress leader Rahul Gandhi’s recent declaration terming the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML) as “completely secular” has triggered a powerful response from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) on Friday. Senior BJP leaders criticised the Kerala-based political outfit as guided by ideologies similar to those of the All India Muslim League, a driving force behind India’s partition, under Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s leadership.

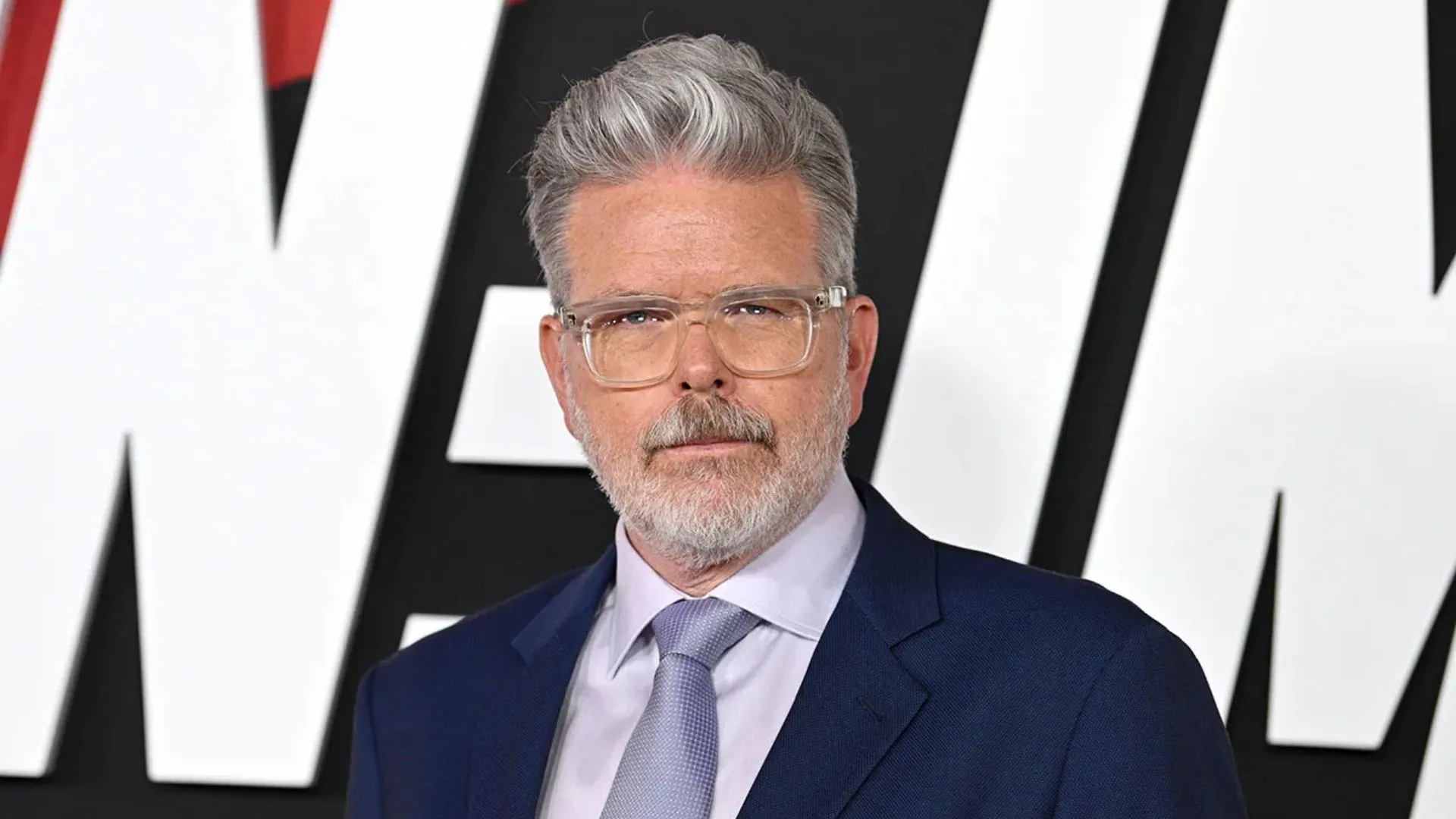

Leading the charge against Gandhi was Union Minister Anurag Thakur, who launched a broadside against the former Congress president. Thakur alleged that while Congress and Gandhi are quick to level accusations of “Hindu terrorism”, they see IUML, a party that, in Thakur’s words, “advocated for Sharia law and wanted separate seats reserved for Muslims,” as secular. This stance, according to Thakur, highlights a deep-seated bias within the Congress party and its leadership.

Thakur further emphasised Gandhi’s political motivations, particularly his necessity to retain a positive image in the Muslim-majority constituency of Wayanad after losing from Amethi. Consequently, Thakur argued, Gandhi finds himself in a position where he has to speak favourably of organisations like the Muslim Brotherhood, an extremist group banned in numerous countries, and the IUML. In Washington DC, as part of his US tour, Gandhi addressed the media defending IUML’s secular credentials. This assertion was in response to a question concerning his party’s alliance with the regional party. Gandhi’s comment, however, drew scorn from BJP leaders back home, who questioned the logic and wisdom behind his statement. Joining Thakur in his criticism were BJP National Spokesperson Sudhanshu Trivedi and Kerala BJP leader K J Alphons. Trivedi aimed to draw a direct link between the IUML and Jinnah’s party, asserting that it was Jinnah’s All India Muslim League that was instrumental in stirring the demand for partition among Indian Muslims. Alphons, meanwhile, took a potshot at Gandhi’s intellect, claiming it to be “limited”.

One of the points raised to challenge Gandhi’s assertions about IUML’s secular nature was the party’s controversial stance on certain social issues. The BJP leaders highlighted that the IUML, in the Malappuram district, had in 2013, proposed to lower the legal age for marriage for girls from 18 to 16, only retracting after strong protests from the opposition.

Amit Malviya, the head of BJP’s I-T department, described Gandhi’s views as disingenuous and sinister, given the historical association of the Muslim League with the religious partition of India. This latest development sheds light on the broader political strategy potentially employed by the Congress party. It seems to indicate a focus on catering to the Muslim constituency. A similar pattern was observed when Congress called for a ban on the Bajrang Dal in Karnataka, possibly attempting to appeal to the Muslim electorate, in light of the Bajrang Dal’s past confrontations with the Muslim community.

This perceived strategy of Congress, often labelled as ‘vote bank politics’, has drawn significant criticism over the years. Critics argue that Congress has overlooked the multifaceted identity of Indian Muslims – one that spans linguistic, regional, and caste dimensions – in an attempt to appeal to a broad Muslim constituency. This approach, critics claim, has led to a disproportionate emphasis on religious issues rather than on crucial socio-economic needs such as education and job creation.

This criticism finds resonance in historical instances like the Shah Bano case, wherein the Congress party allegedly succumbed to pressures from religious leaders, ulemas and maulanas, in the face of a Supreme Court judgement.Critics argue that Congress has a history of leveraging the influence of religious leaders during election periods, while ignoring the broader developmental needs of the communities once elections are over. Critics suggest that this focus on religious issues rather than economic development, jobs, and education has led to the marginalisation of Muslims in India.

The issue at hand is indeed complex, involving an intricate interplay of socio-economic factors, historical biases, and systemic challenges. However, this current episode raises critical questions about the nature of secularism, the role of political parties, and the use of religion in electoral politics. As we move forward, the political discourse needs to evolve towards a more comprehensive and holistic approach that addresses these multifaceted challenges beyond mere election cycles.