Shilpi Rao Narayana was sitting in a corner of the gallery at Karnataka Chitrakala exhibition and was engrossed in completing his line drawing as viewers of his retrospective exhibition, Kalaayana, snapped pictures and carefully examined the intricate lines of his sculptures. He only set down his painting when someone approached and paid close attention to what was being said.

When someone pointed to the drawing he was doing, he shyly flipped open his sketchbook to let the person into his imaginary world. Much like his sculptures, which are mythological figures mostly, his line drawing too is a scene from a story in Mahabharata where Shakuntala is addressing sage Kanwa. “I love Shakuntala’s story,” he mentioned.

At the Chitrakala Parishath, there are not only a few of his sculptures on display but also images of his sculptures that are mounted in temples throughout Karnataka, graph paper measurements for large-scale sculptures, prototypes of sculptures, his anatomical study of the curves of the human body, especially that of the female form, his attempts to perfect the various mudras, calendar art, and line drawings, the majority of which is devoted to the allure of Shakuntala.

Much later, after reading the note accompanying the exhibition written by his son, Vishal Kavatekar who is an assistant professor at the College of Fine Arts, Bengaluru, one can see yet another connection. V Shantaram’s films, who made one of the earliest film adaptations of Shakuntala in 1943 are acknowledged as inspirational.

“He did not attend any art school or undergo any other formal training. He learnt all by himself. So not only films, he also drew inspiration from Dalal Art Studio calendar and illustrations that were published in newspapers and magazines,” said Kavatekar.

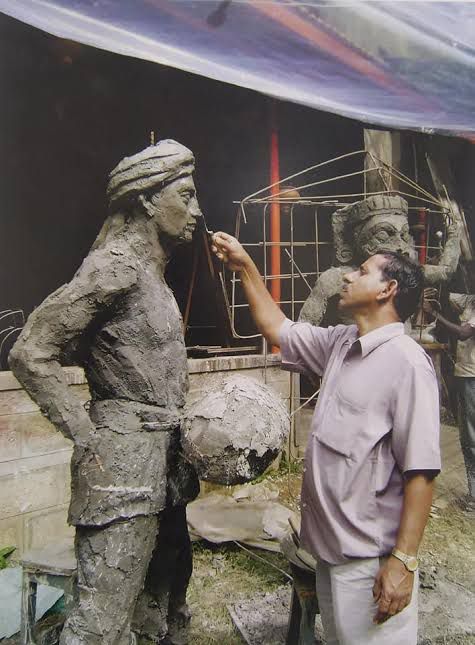

“There was a need for a new style of temple architecture in Karnataka that would adapt to the speed and sensibility of modern times and yet reflect regionalism. Additionally, there was a need for individuals who could work with suitable medium. So, in 1960s and 1970s, with my uncle, sculptor Shilpi K Kashinath, my father started working in cement,” said Kavatekar.

Together, the brothers expanded the possibilities of cement-based gopuras (temple tower) in Karnataka. But while Kashinath took the modernism route, Rao experimented with the existing style until he found his own language of art.

His sculptures stand firm cast in cement. He didn’t always prefer using cement. But it is clear that he has acquired the skill necessary to manage this commonplace stuff over time. His approach might be characterised as a synthesis of knowledge of the past and skilful application of resources accessible in the present.