Higher consumption of ultra-processed foods is strongly associated with an increased weight gain. Researchers at the University of Sao Paulo have calculated the impact of adolescents consuming ultra-processed foods on the risk of obesity.

The findings of the study were published in the journal, ‘Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. There are 3,587 adolescents aged 12-19 who took part in the 2011-16 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). They divided participants in the study into three groups according to the amount of ultra-processed foods consumed.

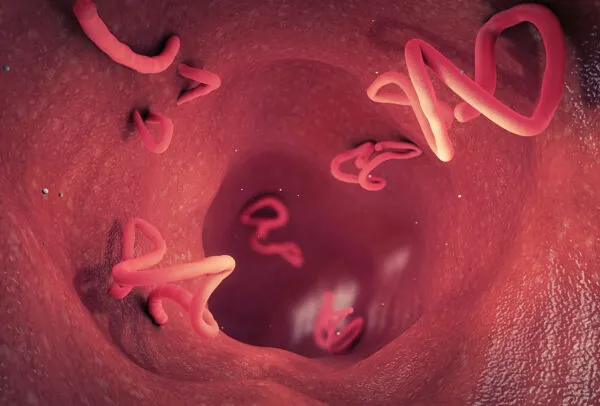

When they compared those with the highest level (64 percent of total diet by weight on average) with those with the lowest level (18.5 percent), they found that the former were 45 percent more likely to be obese, 52 percent more likely to have abdominal obesity (excess fat around the waist) and, most alarmingly, 63 percent more likely to have visceral obesity (excess fat on and around the abdominal organs, including the liver and intestines), which correlates closely with the development of high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia (high cholesterol), and a heightened risk of death.

“There is substantial scientific evidence of the negative role of ultra-processed foods in the obesity pandemic. This is very well-established for adults. Concerning young people, we’d already found that consumption of these products is high, accounting for about two-thirds of the diet of adolescents in the US, but research on the association between consumption of ultra-processed foods and health outcomes, including obesity, was scarce and inconsistent,” said Daniela Neri, first author of the article.

Led by Professor Carlos Augusto Monteiro, the NUPENS team was one of the first to associate changes in the industrial processing of food with the obesity pandemic, which began in the US in the 1980s and has since spread to most other countries.

Based on this hypothesis, the group developed a food classification system called NOVA, based on the extent to which products are industrially processed.

The system informed the recommendations in the 2014 edition of the Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population, which emphasized the benefits of a diet, based on fresh or minimally processed foods, and emphatically ruled out ultra-processed foods ranging from soft drinks, filled cookies and instant noodles to packaged snacks and even an innocent type of whole meal bread.

Generally speaking, ultra-processed food and drink contain chemical additives designed to make the products more appealing to the senses, such as colourants, aromatizers, emulsifiers and thickeners.

Many ultra-processed foods have high energy density and contain a great deal of sugar and fat, all of which contributes directly to weight gain,” Neri said.

“But even low-calorie products such as diet drinks can favour the development of obesity in ways that go beyond nutritional composition, such as by interfering with satiety signalling or modifying the gut microbiota,” she added.

They used data collected by a methodology known as 24-hour food recall, in which subjects are asked to report all foods and beverages consumed in the previous 24 hours, detailing amounts, times and places.

Most of the participants included in the analysis (86 per cent) were interviewed twice on this topic, with an interval of two weeks between interviews.

The adolescents were divided into three groups on the basis of this information: those in whose diet ultra-processed foods accounted for up to 29 per cent by weight, between 29 per cent and 47 per cent and 48 per cent or more.The researchers also used anthropometric data, such as weight, height, and waist circumference.

These measures were evaluated against age- and sex-specific growth charts approved by the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

“Total obesity risk was estimated on the basis of body mass index, or BMI, which is weight [in kilos] divided by height squared [in meters],” Neri said.

“We used waist circumference to assess abdominal obesity, and sagittal abdominal diameter, a less well-known parameter, as a proxy for visceral obesity,” she added.

Measuring sagittal abdominal diameter, she explained, is an indirect and non-invasive method to estimate the amount of visceral fat, “The subject lies down and we use a caliper or magnetometer to measure the distance between the top of the gurney and the region of the belly button. The softer subcutaneous fat falls to the sides, and the visceral fat, which is harder, stays in place.