An age-old debate that kept scholars, citizens, administrators, and politicians equally worried is about the capacity to govern. In older Indian archives Kautilya’s Arthshashtra presented a blueprint for Chandragupta Maurya’s governance and linked money, military and markets to build king’s capacity to govern. Post-war scholars such as Eldon L. Johnson and later policy analysts like Yehezkel Dror generated enormous discourse on ‘capacity to govern’. A critical survey of these discourses may highlight the capacities required to govern especially in these election times when political parties are spewing toxicity and honey together to confuse the constitutionally prescribed real sovereign, ‘We the people’ who watch in awe or in silence for the drama to unfold. A look at those capacities which can govern would resolve much of the real sovereign’s worry.

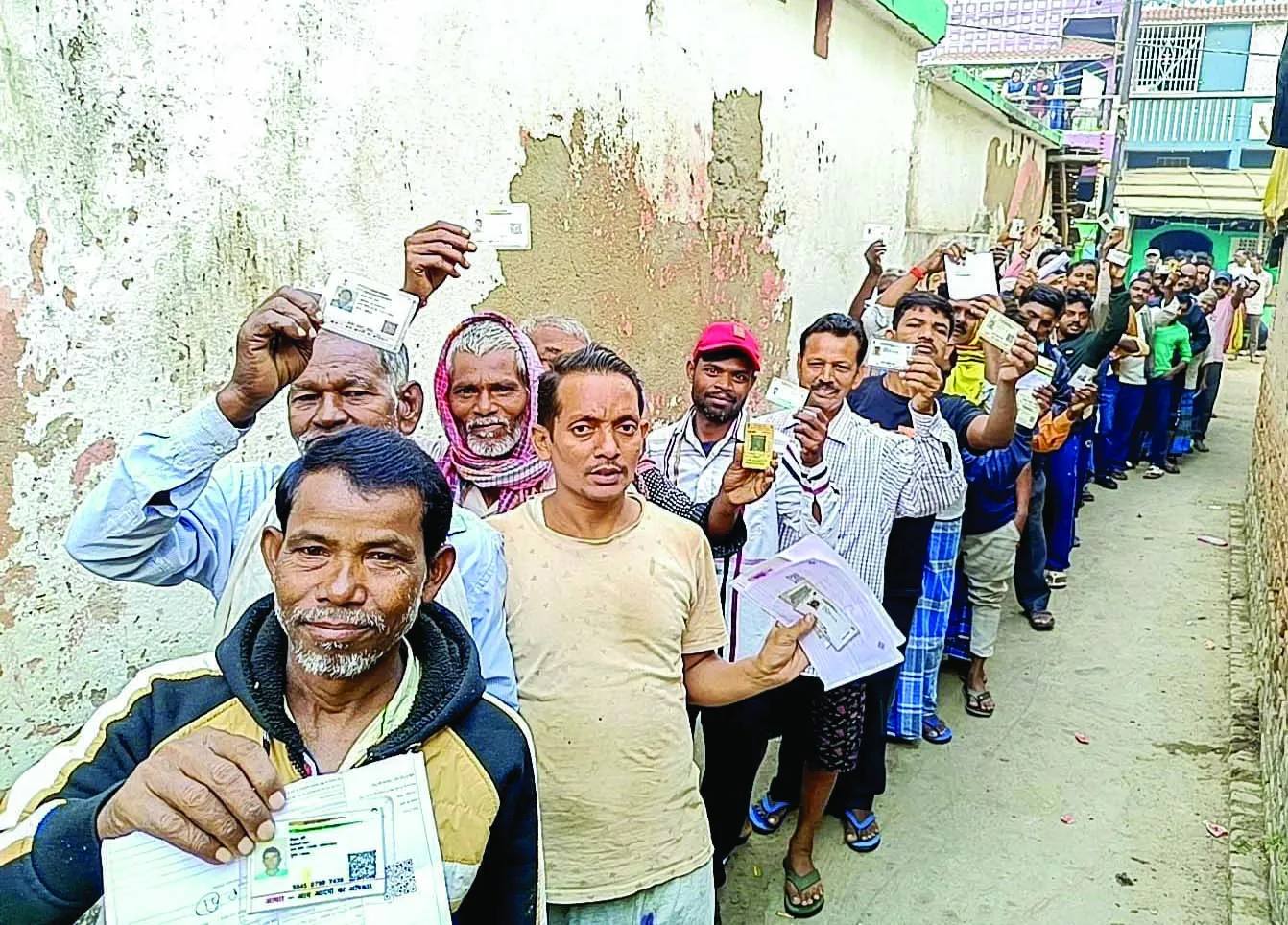

Most books on politics begin with a famous flourish that ‘man is a political animal’. Remove ‘political’ and ‘animal’ is left behind. An animal can only be befriended, ennobled and cultivated through association, care and communication which incidentally also form three basic characteristics of democracy. A deluge of television channels’ breathless loud discourses on democracy in these pre-election times, treat elections as a key characteristic of leaders’ commitment to democracy. He who holds elections in time and without fear of even the pandemic is a perfect democrat. The Election Commission innovated elections in many ways; elections are outdoing the pandemic fears, outstripping the digital divide by declaring online canvassing or digital campaigns, beating out gender activists who repeatedly warned that women have no or very little access to computers in most areas! This noble activity of holding elections has now become a defining line of a democratic state. However, on deeper analysis, one can place elections much lower in the hierarchy of democratic ideals. Many valuable and indispensable ideals sustain democracy in the world of today nonetheless because democracy definitely outstrips every other system in its capacity to govern, the easiest justification for a thunderbolt state is that of holding timely elections. Notwithstanding, democracy is the best system not because it rises from the debris of elections but for its ability to elicit association, care and communication in which creativity, ingenuity and trust could grow.

However, the rapidly increasing numbers below poverty line during this pandemic are fearfully asking one question if elections are really so necessary? The capacity to govern is government’s capacity to sustain democracy and this is not emanating from elections but from an ubiquitous understanding of freedoms that citizens and institutions treasure. This capacity is what Johnson in his famous 1955 speech explained as .. ‘that pervasive something which lies between institutions ….that force which holds the institutional sphere in their orbits’. What is that pervasive something? Ethics, law or morality? With our nation currently torn between religious groups, frequently changing regulations, arm-twisting FCRA cancellations, restricting corporate social responsibility, shrinking university- press freedom and repeated elections, what could define capacity to govern?

One could go to Mahabharata to find answers in Krishna-Arjuna unmatched conversation on ‘What is ethical in a battlefield? In Dharmashstra’s Niti and Niyama being closest to ethics and morals respectively, the former signifies right conduct based upon principles while the latter on moral rules indicates right action through subjective personal experience. The Hindu lexicon of ‘Dharma’ established right conduct which goes beyond mere lenses of ‘niti’ and ‘niyama’. The ancient law books referred to as the books of moral duties such as the ‘Dharma Shastras’ have innumerable discourses on the nature of governance and the right conduct of administrators. The Dharma Sutras such as The Gautama Sutras, The Apastamba Sutras, The Vashishta Dharma Sutras, The Baudhayana Sutras, The Srauta Sutras, The Smarta Sutras etc. are long narratives on capacity to govern with definable principles of ethics and morality. The Puranas strived to narrate the embeddedness of the principles of morality and ethics into law. The Panchatantras and its English equivalence in Aesop’s Fables were simply lessons in public morality on loyalty, trust, sycophancy, acquisition, resource sharing and leadership. In essence, the Indian heritage emphasized a notion of ethics in public life as a ‘design to conquer self which emphasized a clean political life and inclusive governance. Most of these texts are valiantly critical and hateful of caste-based titles of ‘Brahmanas’ for the legitimate award of this title is through enormous learning, understanding and practice of knowledge, ethics and morality. For example the two quotes from Vashishtha Chapter III which is identical to Manu XII,(114) castigate a Brahmana who tries to obtain this title simply on the basis of caste and not knowledge. It suggests that even an animal is superior to a Brahmana who does not have the knowledge of niti and niyama: ‘An elephant made of wood, an antelope made of leather, and a Brahmana ignorant of the Veda, those three have nothing but the name (of their kind).

Democracy is inherently legitimate due to its deep consciousness to consultative process. Take for example the making of law. Law is a transaction of three minimum participants ie; person with interest protected by norm, person whose conduct is in question and third person who mediates or interprets the norm to enforce a judgment. This makes law a socio-communicative process that depends for its intelligibility on the existence of persons who are not participants in the underlying transaction. Much in democracy is bonded together due to intersubjectivity where speech is less necessary than a cognitive understanding without speaking as people meet, watch each other and share public spaces where such understanding is believed to exist intangibly.

The universe may be interpreted differently by different individuals and specifically own a cultural fixation. Therefore, it doesn’t have to emerge out of a transaction. The views on morality may also sometime appear myopic and localized such as animal sacrifice, vegetarianism and worshipping spirits. Many of these may not formally be included in laws, are not enforceable and remain confined to a universe of obscurity. Ludwig Wittgenstein in his Philosophical Investigations explains that “Our subjective conceptions of right and wrong not only are indecipherable from without, but they are evanescent from within.” So administrative action ought to possess moral grounds of action as well as its visible logic. Do current politics abide by this moral principle?

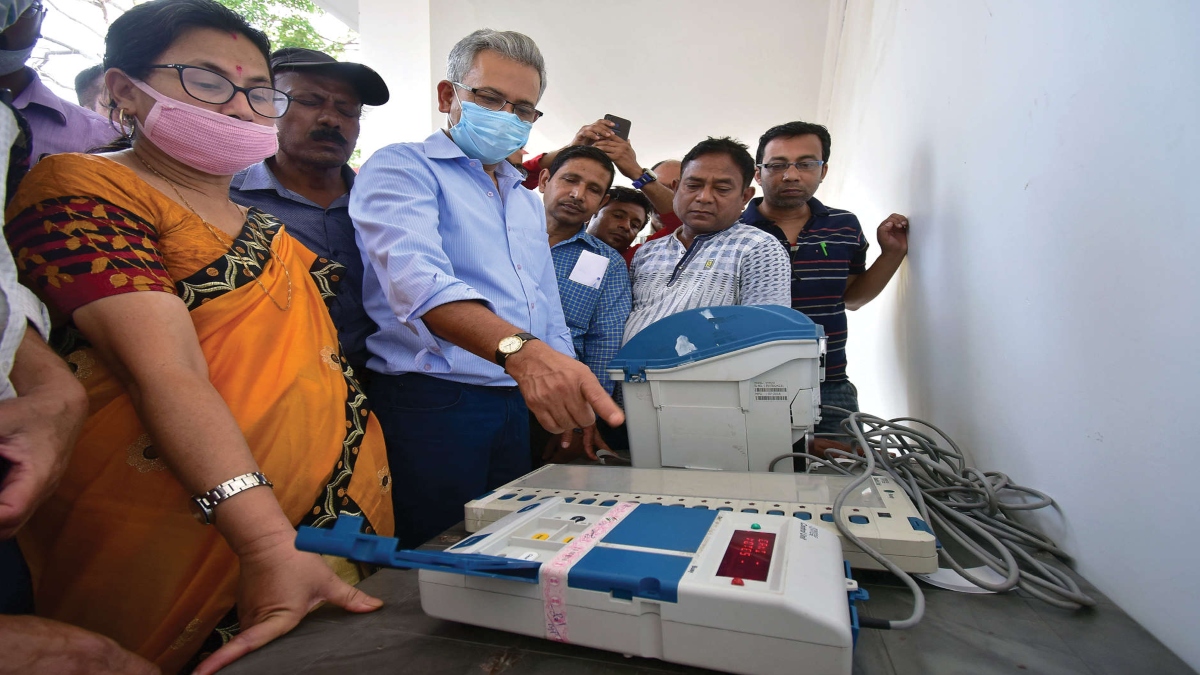

The capacity to govern has been challenged by many mistakes that governments commit intentionally or inadvertently. One such mistake that rulers make is in treating prosperity as greatness, which is not. An undue focus on achieving prosperity leads to a rush for efficiency and if that is not available in an organic manner then governments digitize and increase efficiency through e-governance processes. In doing so the government drops out of a natural organic support system that which was its real strong mast against rough weather. Much of the currently declared digitized elections are likely to pass the test of law but not of ethics. The world of ethics and morality simply transcends the black letter law and exposes many myths which judges and lawyers live with and apply in their many judgements in the courtroom.

There is much that can be said on digitized platforms that political parties are designing for their election campaigns.It is difficult to accept how would voters become knowledgeable before they cast their votes? Their ingredients to right voting is as follows;

To watch a digital campaign they need electricity but despite the Saubhagya Scheme of government to provide electricity to each home the quality of electricity shows much disappointing picture. The Ministry of Rural Development in 2018 brought out that only 16% homes received one to eight hours of electricity daily, 33% received 9-12 hours, and only 47% received more than 12 hours a day. As soon as the electricity comes, men and women get to their machines and equipment which are electricity operated.

Next in requirement is a computer or a smartphone but only 11% own a computer and mere 24% own a smartphone. Even if they have one, the penetration of digital technologies in India is as low as only 24% use internet at home with 42% in urban areas and only 15% households have access to internet in villages. As women are voting in large numbers, the digital platforms are likely to discourage them from voting and this may do much harm to Congress prospects in Uttar Pradesh where Priyanka Gandhi Vadra has mustered a huge women following with her regular interaction with them over the last two years. As per the Internet and Mobile Association of India Report 2019 only 33% women have access to internet in contrast to 67% men. In villages it’s shockingly worse at 28% and 72%. The data from the poorest or the caste marginalized communities is also not encouraging. To use digital platforms for conducting a most sacred duty of democracy seems full of mischief or a design.The digital platforms are likely to bring new challenges to the election process which would need more ethics than technology and law to handle it.

To the masses, election campaign is likely to be an obscurantist’s delight where ideas and thoughts would be eclipsed as in a TV soap, communities would act as passive informants rather than dynamic critiques. These elections would become a theatre of the muted, or to use a phrase from Pierre Emmanuel in What Have I to Defend in Confluence, I (1952) ‘The mechanical suppression of Silence’ and in turn, may act against the real spirit of sustaining democracy or developing a capacity to govern.

The writer is president of Network Asia Pacific Disaster Research Group (NDRG), Senior Fellow at the Institute of Social Sciences (ISS), and former Professor of Administrative Reforms and Emergency Governance at JNU. The views expressed are personal.

Democracy is inherently legitimate due to its deep consciousness to consultative process. Take for example the making of law. Law is a transaction of three minimum participants ie; person with interest protected by norm, person whose conduct is in question and third person who mediates or interprets the norm to enforce a judgment.